Essays / Scott Watson

Urban Renewal: Ghost Traps, Collage, Condos, and Squats

Download PDFThe tides flow in and out and you adjust your rhythms to them.

—Paul Spong[1]

Vancouver has been periodically mythologized as the leading art scene in Canada.[2] In the 1950s, abstract painting derived from British and European (more than from American, as one might have expected) examples along with the establishment of a Los Angeles-influenced West Coast modernist architecture inspired some enthusiastic observers to declare a “renaissance.â€[3] Art travellers, largely commissioned by the National Gallery of Canada, discovered a small coterie of artists, architects, musicians, and teachers who had plunged themselves into twentieth-century aesthetics. But in an international or even national context, one would have to admit that the advent of modernity in domestic architecture was very late in arriving in Vancouver. The ï¬rst post and beam homes with flat rather than gabled roofs were built in 1939, just on the eve of the war that forestalled any further such development until the late 1940s. From that time until the early 1960s, modernism seemed to flourish. Most of the city’s painters (we are talking of about twenty people) lived in architect-designed suburban homes. While it is usual to think of the work of these painters as involved with nature and the motifs of forest, mountain, ocean, and atmospheric effect, utopian and dystopian images of the city abounded in their work. Although often described as basing their abstractions in the landscape, a strong figurative and even expressionist current is found in their work. It is as though they imagined a city that was yet to come into being. The second “renaissance†was in the 1960s, and the third began in the 1980s.

In the 1960s, it was asserted that this city led the nation in experimentation and the embrace of new ideas in the arts. We do not need to examine the speciousness of that claim, nor why it would be made of such a small provincial city. One celebrated factor was Vancouver’s “West Coastness†in a world that was taking the pulse of California’s hippie cultural rebellion. The counter-culture of consciousness raising, Tibetan Buddhism, faux agrarianism, wilderness worship, LSD, and sexual exploration found its biggest Canadian colony in Vancouver. This “West Coast Thing†was a social and aesthetic context for Vancouver art in the 1960s. It is remarkable, despite the growing — or abiding — interest in the 1960s all over the world, that so much artistic work from this period in Vancouver is lost and, cruel to say, how many sixties artistic careers subsequently entered the twilight. This is especially odd in a city whose artistic community’s boosterism seems to know no limit and where the 1960s are forever recalled as a golden time of artistic freedom in lived and transmitted memory. This contribution includes a discussion of several key works from the sixties and a description of the counter-cultural context from which they are not easily divorced.

First experimental ï¬lm and then video thrived in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fugitive nature of these media is one cause of lacunae in our art history. Other, darker historical forces also intervened. Stan Brackhage-inspired ï¬lmmaker Sam Perry, who took his own life after drifting into a psychosis that might have been provoked by LSD, pioneered psychedelic projections at rock concerts and made ï¬lms about his travels in Tibet in 1962. His major work was the 1966 Trips Festival, where he and his artist colleagues mounted a projected sensorium of ï¬lm, slides, and moving liquid utilizing over ï¬fty projectors. This was a three-day extravaganza that featured Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Grateful Dead, as well as other San Francisco and local bands.[4] Perry was a catalytic ï¬gure whose ï¬lms are perhaps utterly lost to us. They are described as cut-up montages, influenced by Brion Gysin and William Burroughs. Perry was interested in the possibility of ï¬lm triggering a consciousness-raising experience; thus his experimentation with multiple projection overlays and the organic, psychedelic look of coloured oils swirling in water. The multiple projections were an attempt to make what poet Jack Spicer (who read and lectured in Vancouver in 1965) called “Ghost Traps” from the image swirl you see when your eyes are closed. Perry called this ï¬eld the “Dot Plane.â€[5]

The Trips Festival was the most elaborate of the multimedia sensoria of the 1960s. These multimedia events, interestingly, follow the “institutionalization†of avant-garde experimentation in galleries and perhaps augured the darkened realm of projected images that pervade contemporary museums decades later.[6] A broad consensus held that synaesthesia was the model for the art of the future. Academics and people whose modernist convictions had gelled in the 1950s or earlier entered the sensorial realm, convinced that it involved consciousness-raising aided by technology and furthered by the progress of liberal democracy spurred on by Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan. The LSD users and those converted by the Dalai Lama entered the sensorium convinced of the uselessness of liberal democracy. They were convinced of the viability of anarchism (or the theocracy of Tibetan Buddhism), spurred on by William Burroughs and Alan Ginsberg. Utopia and dystopia were both around the corner. “Paranoid†about the CIA, Perry was, in fact, under the treatment of a psychiatrist who had been a CIA operative and who decades later was sentenced to four years in jail for turning female patients into sex slaves.[7]

In the era of R. D. Laing, Norman O. Brown, and Fritz Perls, madness was a political issue and psychiatry a weapon of the state.[8] In such an atmosphere, acts of documentation and witnessing took on an urgency belied by the conceptualistic cool artists often adopted as a public stance. Amidst the psychedelic radiance of fragmenting, permutating organic rhetoric, are works that are primarily documentary or whose character is of a document. Works produced at a time when so much was ephemeral and committed to process survive projects of documentation, preservation, and cataloguing. The nature of the sensorial meant that they eluded documentation, but they informed other more mundane activities, especially new ideas of the urban experience.

By the 1980s, the city and its suburbs had become a major topic in photographic images by Vancouver artists and for a third time Vancouver was touted as a centre for contemporary art. In this era, too, the demolitions that prepared the site for Expo ‘86, the sale of 173 acres of downtown property to a single developer, and accelerating incursion of suburban tracts into “wilderness†mountains and the agricultural Fraser Valley provided a stimulus for images of the violent confrontations between capital and nature that occur in British Columbia, which had earned by then the sobriquet, “Brazil of the North.†As noted elsewhere, the city and the idea of the urban preoccupied artists in the 1950s.[9] The present argument is that this was also the case in the 1960s, although expressed through different practices and modiï¬ed by various activist agendas of the day. However, this is not to suggest that a “theme†runs through Vancouver art and that we can call this theme “the city†or “the conflict between the city and its natural setting.†Art is more complex than that, and the aesthetic programmes of the 1960s had an imperative to imagine revolution.

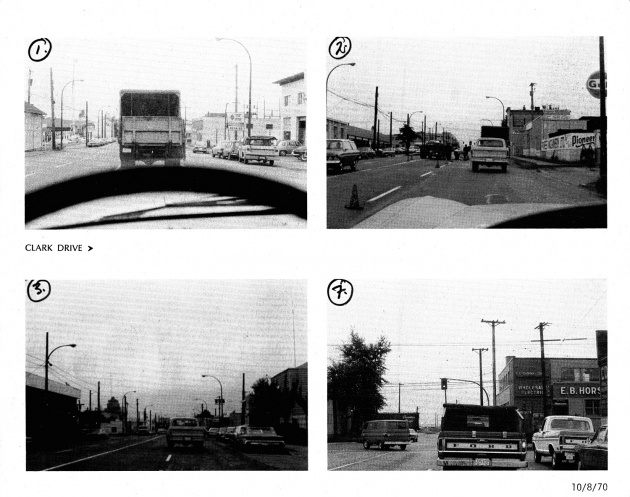

The city became—for the generation of Iain Baxter, Jeff Wall, and Ian Wallace — the means to visualize the abstractions of capitalism that were transforming the city. It is interesting that the juvenilia of artists such as Wall or another city documenter, Christos Dikeakos, or even architect Robert Kleyn, includes large, ambitious, perhaps Situationist-inflected, documentary dérives that include works such as Wall’s Landscape Manual (1969) and Christos Dikeakos’ Instant Photo Information (1970). These are clearly works of art that involve documenting, but in a way that was influenced by William Burroughs, Ed Ruscha, and Robert Smithson. The text of Landscape Manual does not seem as prescient today as the pictures and the fundamental principles of disinterestedness and the aleatory dérive that “produced†them, focusing on and deï¬ning what Wall called the “defeatured landscape.†The writer Dennis Wheeler responded with the “defeat(ur)ed landscape.â€[10] The text, like so many texts produced by artists during these years, indicates the importance of consciousness to early conceptualist thinking. As the anthology edited by Wall, Wallace, and Duane Lundon, Free Media Bulletin No. 1 (1969), indicates, thinkers called upon to address this question included Alexander Trocchi (a member of the International Situationist movement) and Marcel Duchamp. A project like Architecture of the Fraser Valley (1972) produced by a group that included Rodney Graham, Robert Kleyn, Duane Lunden, and Frank Johnson (aka Ramirez[11]), involved artists and their methods in the production of a document. The project was to document the disappearing pioneer (Victorian era) buildings of the Fraser Valley, the oldest European settled part of the Vancouver area. Partly systematic but partly given over to the random, the driving and search become part of the text or the proposition that revealed a “culturescape†in the landscape that, in turn, revealed the economic forces at work in the production of both. Graham would later revisit the drive through the Fraser Valley in his work Halcion Sleep (1994). As document /dérive one would also include the suburban documents of Iain and Ingrid Baxter working as the N.E. Thing Company and works such as the monumental background/Vancouver (1973–74) by Michael de Courcy with Taki Bluesinger, Gerry Gilbert, and Glenn Lewis. De Courcy’s main work during this time was documentary; he is among the main witnesses to the performances of Intermedia (1967–71) and the living situations at the Maplewood Mud Flats and Babyland (Robert’s Creek).[12]

In the 1960s works appear as books, photographic archives, slide shows, lists, grids of images, and ï¬lm. They possess something of the character of collage or montage and derive their energies from sources as varied as Russian avant-garde art, the Situationist movement, and Minimal and Conceptual art.[13] Vancouver artists and many of their contemporaries felt the need to witness and register the dramatic changes to cities occurring at this time. In some sense it is wrong, however, to highlight this interest in documentation without contextualizing the often antagonist aesthetic positions that motivated these projects. Those antagonisms are crucial to what followed from the sixties. Although the innovations of the late 1970s and early 1980s are everywhere prescient in the sixties, it is hardly a linear, determined path from point A to B. For example, Iain Baxter pioneered the back-lit Cibachrome in Vancouver. He owned the ï¬rst Vancouver franchise for the Cibachrome process and began making light boxes in 1967–68. Among his topics were the urban “ruins†of Vancouver’s suburbs and the vernacular of their sprawl. One cannot, in any meaningful way, connect these light boxes with Jeff Wall’s later adoption of the form around 1978. It would also be reckless to connect the loop presentations of Glenn Lewis, circa 1969, of urban intersections with the later emphasis on loops in the work of Rodney Graham. But one could argue in good faith that a recent work like Graham’s The Phonokinetoscope (2002), with its acid rock score and LSD vision, revisits the origin of Vancouver experimental ï¬lm and sensorium environments in the psychedelic era. But it would not be correct to see in Lewis’ 1970 Forest Industry — a two-hour plus, real-time ï¬lm of Lewis walking through the forest—anything of the ethos that animates Graham’s industrial forest confrontations. It really is the other way around, but no less interesting for that. The work of the 1980s to the present allows us to think about the work of the 1960s in a new way, impels us to return to it and ask again for its witness. Lewis’ ï¬lm, a multimedia “sensorium,†showed him in real time demarcating with tape a square kilometre of forest. The ï¬lm was projected from a revolving stand that circled the room once during the screening. Live and electronic music was provided by Martin Bartlett. [14] Even between contemporaneous (more or less) works, it might be rash to draw too tight a connection. But it is tempting to see more than parallels between Perry’s “Dot Plane†and the concretizations of Colour Bar Research, as carried out by Gary Lee-Nova, Michael Morris, and Vincent Trasov between 1968 and 1972. Even as late as Dikeakos’ The Collage Show (1971), the happy inclusiveness of the multimedia sensorial events was still alive.

The exhibition included the surrealist, anarchic, and more sober, bureaucratic conceptual. Ian Wallace’s Pan Am Scan (1970) and his resilient Magazine Piece (1969–) were ï¬rst exhibited in this exhibition, along with what Wallace described as his “normal†collages. “Collage for me is not so much a speciï¬c genre of picture-making [collages] as it is a principle of semiotic order, yet there is complete continuity in this principle between the ‘normal’ collage and other works, such as my Magazine Piece or Pan Am Scan.â€[15] One wishes Wallace had elaborated on what he meant by semiotic order. At the time, he would have been referring to Roland Barthes. His insistence on continuity—whatever the guiding trope—is what seems remarkable today when the intertwining strands of ideas that informed the making of art in this period have since been so thoroughly categorized as marketing tools in retrospect. But perhaps semiotic order is the order of Magazine Piece, an ingeniously simple strategy for producing a wall montage that appropriates a ready-made magazine and splays it out so that it reads as a totality, like a map. Thus, the episodic nature of magazine narrative is overcome by a demonstration of structure that appears to indicate montage animates the mass media as a manipulative tool. The Collage Show contains many references to the notion that collage and montage had the potential to disrupt this regime.

From the mid 1950s to the late 1960s, there was not a great deal being built in the downtown and inner neighbourhoods of Vancouver.[16] The artistic flight to the suburbs that occurred after the war was part of that economic picture and indeed a symptom of the “problem.†The suburbs were expanding, and the city’s tax base was languishing. Vancouver was subject to the global trends of capitalism and especially those that affect port cities. In the 1960s almost every major city in the capitalist world saw enormous demolition, reconstruction projects.[18] This urban transformation at once spoke of changes in how capitalism worked and in how, to use Henri Lefebvre’s term, the “production of space†revealed the inorganic abstractions of capitalism in the deep excavations and walls of grids and glass of the new downtown cores. On a more quotidian level, these changes undermined and eventually destroyed the infrastructure of avant-garde art and the other undergrounds that intersected art production. The transformation of the city is also a major subject of avant-garde work, as if by witnessing the death of so many strands of the urban texture, art witnessed its own death or the death of its bohemian lifestyle and revolutionary ambition.

By the 1960s, the large Victorian and Edwardian building stock that existed on almost every street in the city had deteriorated, much of it held by offshore interests. It was in such locations that one found places like the Sound Gallery/Motion Gallery (1965–67), Image Bank (1968–72), Intermedia (1967–71), New Era Social Club (1968–72), and, ï¬nally, in 1973, when a group of artists bought a building, the Western Front (established in 1973) to create a secure bastion of rebuke (it still exists).[19] Old vaudeville theatres housed performance art, while artists lived in old urban houses, unlike their elders—the generation of modernists who lived in suburban post and beam houses. The older building stock was conveniently cheap and not in demand from other users. But it stood for values. It was excoriated by modernist planners who declared it “illiterate.â€[20] Thus, the older buildings, especially houses, stood for improvised communal living in buildings constructed before the war; development stood for “planning†and the organization of daily life by corporations and the state. Schemes began to float to reconstruct the downtown and inner neighbourhoods. Many of these were blocked by citizen activism.[21] The battles were ferocious, pitting developer politicians and their access to police force against squatters, hippies, rioters, and an emerging militancy among ethnic groups. Even with such victories, the city lost a large inventory of Edwardian buildings, and transformation from Edwardian outpost of Empire to what Jeff Wall has called the “generic city†began in earnest. The inexorability of this appearance of the generic city occupied the interest of some artists; other artists focused on the signs of resistance to this phenomenon.

At the advent of what we now call postmodernism, the doomed Edwardian building inventory that provided bohemia’s living, studio, and event spaces also provided an aesthetic opposed to Brutalism, the heavy concrete fortress style of public buildings that had arisen in response to the riots and demonstrations of the 1960s. Late Victorian and Edwardian furniture and bric-a-brac furnished communal houses. In these spaces Art Nouveau was revived and deployed to advertise concerts and events. Rejection of the “brutality of the new†was, in essence, a very real concern about the disappearance of places to live, eat, congregate, exhibit, and perform. In defense of a crumbling inventory of modest, poorly built pioneer-era wooden and brick structures, the art community of the day rejected not only the Brutalist idioms of the 1960s and 1970s, but the gentler suburban modernism of the 1940s and 1950s. Or to be more precise, the authoritarian, normalizing, “design for living†modernism, with its unarticulated suppression of libidinal circulation, was an anathema for the generation of the 1960s and 1970s. The hippie movement as appropriated by fashion and popular music adopted Edwardian and Art Nouveau as its style of protest and renunciation of consumer/spectacle society.

In 1966, as a stimulus to development and to increase the value of urban real estate, legislation introduced regulations that allowed strata ownership of apartments in British Columbia. The condominium building boom that followed has since transformed not just the appearance of Vancouver, but the texture of everyday life and the notion of what constitutes a home. The condominium was an advance in capitalism’s drive to commodify every aspect of living and to reorganize wealth. The death of Vancouver’s night-life and the closing of its night-clubs followed as a consequence of condominiumization. In short order, the artist community and bohemian life moved from the city’s downtown West End to Kitsilano, where it was eventually snuffed out in the late 1970s. Coincidently, a landmark artwork of 1966 was Baxter’s Bagged Place. For this work Baxter installed a fake four-room apartment in a gallery and wrapped the rooms and their contents in clear plastic. The idea, expressed in the invitation card, “For Rent, Bagged Place,†was interpreted at the time as an invocation of consumer society. “Bagging†read as packaging; packaging read as commodiï¬cation. Thus, Bagged Place, although only for rent, was the ï¬rst local artistic rendition of the condominium. Homelessness and apartment living were, coincidently, the thematic underpinnings of Robert Altman’s 1969 ï¬lm, That Cold Day in the Park, one of very few Hollywood movies shot in Vancouver that is actually set in Vancouver. As Altman’s ï¬lm was among the ï¬rst industry movies (for example, with movie stars) to be shot in Vancouver, it received a huge amount of local press attention.[22] From almost the outset of the commercial ï¬lm industry in Vancouver there was interpenetration with the art world, as artists worked for ï¬lm studio art departments. As in Los Angeles where the economic basis in a fantasy industry and the pornography of celebrity informs the works of so many artists, the movie industry began to provide more than just jobs for artists. Like the mirrors in malls meant to reflect space in a mesmerizing inï¬nity of receding boxes, the movies showed how the production of space and the production of the spectacle interact. Interestingly it transpired that it was the city’s older building inventory that Hollywood valued, thus giving new economic rationale to the crumbling inventory. In Vancouver there grew within the art community an increasing fascination with the transformation of the entire city into a façade.

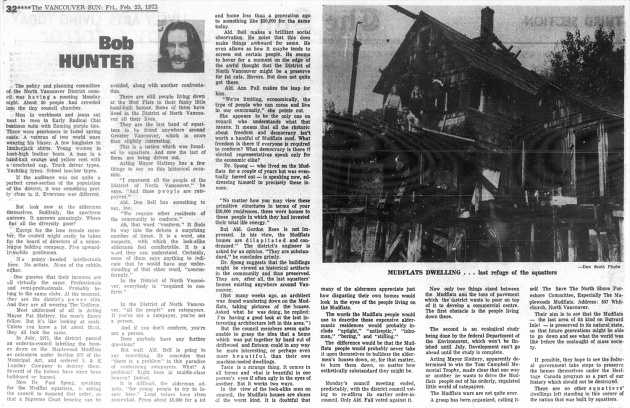

In 1971, most of a squatter community on the Maplewood “intertidal†Mud Flats, near where Malcolm Lowry had written Under the Volcano, was burned to the ground by civic authorities, ostensibly to clear the way for private development. Squatting in the intertidal zone is as old as Vancouver and is an important part of the history of the city. (Finn Slough on the Fraser River is a squatting community still present in 2005; it was established in the 1890s.) Intertidal squats have been established and last largely due to the ambiguity of jurisdiction over the intertidal area. In Canada, private property, regulated by cities and their zoning laws, can extend no further than the mean high tide mark. The intertidal zone is the jurisdiction of the federal government. The 1971 ofï¬cial arson marked a turning point, or point of no return, in the transformation of metropolitan Vancouver. The Maplewood intertidal squat was constructed not just alternately to new condominium living, but in active polemical opposition to it — indeed, not only that but even in opposition to humanist modernism of the 1950s. The hippie aesthetics of the Maplewood squat derived entirely from the crumbling civic inventory. The Maplewood squat was a highly symbolic episode in a dynamic tension between values still active today. It was both urban and rural: it was a bit of country ringed by the city. Backed by a liminal forest that separated it from the growing bedroom suburb of North Vancouver, it faced the Shell Oil reï¬nery located across the waters of Burrard Inlet.

Squatting became symbolic of everything that was slated for demolition and for the possibility of protest. This was authentic uncommodiï¬able human habitation, the polar opposite of the condo. Squatting was deployed to prevent the building of a hotel at the entrance to Stanley Park. (The site is today an extension of Stanley Park.) And squatting became a utopian model for self-determined “village,†self-sustaining communities in a city whose neighbourhoods were being razed for condo high-rises. The intertidal location was ruled by diurnal rhythms and lunar cycles, so available for parables of the rightness of living in harmony with nature. Tom Burrows, who built and lived at the Maplewood Mud Flats, produced an important body of “intertidal†sculpture there, and later embarked on a world-wide project, in 1976, to document squatting. Burrows’ Maplewood house is depicted in Ian Wallace’s seminal triptych, La Mélancolie de la Rue (1973), where it stands for the whole disposable human past in juxtaposition to the bulldozed landscape of the new suburbs and the Brutalist façade of the new Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Wallace’s work inaugurates “photo-conceptualism†in Vancouver with a picture of Burrows’ mud flat house. Burrows’ house and his sculptures were, in the early 1970s, published in artscanada (February/March 1972) in the context of other artists such as Dean Ellis, who also made “Smithson-inspired†ephemeral constructivist works in the intertidal zone. Burrows’ photographs of his mud flat sculptures stand as among the most eloquent documents of the period. Bricolage constructions inspired by the drawings of Kasimir Malevich and meditations on mirroring and symmetry involved him in a pursuit of formal questions.[23] But subject also to the action of the tides and the incomprehension of the hippie squatters, who would salvage material from them, they were liminal in every sense, most importantly in the meeting of the organic and the inorganic. Having been a student in London in 1968, Burrows was among the most informed about Situationist anti-aesthetics of all Vancouver artists (as were Wall and Wallace, who also lived in London during this time). The title of his article on his work at Maplewood, “only take for granted the things you can touch,†vouches for the distinction to be made between the image industry and the hand-built house.[24]

The importance of the Maplewood squat to its contemporaries is evidenced in two ï¬lms about it. Mudflats Living (1972) was a National Film Board of Canada production. The other was an independent documentary, Sean Malone’s Livin’ in the Mud (1972). Mudflats Living is journalistic in style, suitable for broadcast. Livin’ in the Mud is a more polemical and poetic involvement with the situation at hand. But both ï¬lms are inflected with some of the language of the more experimental ï¬lms of the time. Both documentaries focus on the continuity of the Maplewood squat with the independent spirit of the resource worker “Old Mike,†who lives by scavenging and salvaging wood: he stands for old country values. He is not an agrarian ï¬gure. He is a cast-off resource industry worker and kind of a pet, rather than revered elder, for the hippies who represent Maplewood in the ï¬lms. Both ï¬lms are dominated by the camera hungry, gently Mansonesque eloquence of Dr. Paul Spong, who was already preparing the “Save the Whales†campaign, which would turn the Vancouver-based, anti-nuclear-testing Greenpeace to world-wide ecological activism. Spong had been ï¬red from the Vancouver Aquarium for suggesting that the whales were evolved sentient creatures.

From squatting and demolition arose bricolage and collage. These came to be the idioms that best expressed the constellation of values brought to bear in the defense of the old city, which in turn accrued other organic values like barnacles on piers. Since the revival of interest in Dada in the late 1950s, collage had been the instrument with which to integrate the exponentially increasing “image world†of postmodernity. The multimedia sensorium with its image overlays was collage as Gesamkunstwerk (integrated work of art); the squats were bricolage as Gesamkunstwerk. The collage artists of this time include bill bissett, Christos Dikeakos, Gary Lee-Nova, Gregg Simpson, Ian Wallace, and many more. Bricolage informed the intertidal sculptures of Tom Burrows and Dean Ellis. Willie Wilson and Al Neil were the Gesamkunstwerk bricoleurs. Wilson was featured in Mudflats Living, showing a part of his enormous collection of scrap culled from the demolition of Edwardian and Victorian housing. Wilson, as a supplier of salvage from old houses, worked constructing and decorating sets for Robert Altman’s second ï¬lm to be made in Vancouver. McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), a frontier parable in which hippie ideals played out against the long arm of speculative interests, was being ï¬lmed on the North Shore in the mountains above the Maplewood Flats.[25] As the sets were being built up the mountain, a hippie “Pleasure Faire†was being constructed on the flats: another ersatz village that mirrored the one for the movie that in turn mirrored the squat itself. The movie and the Pleasure Faire showed that the authentic squatter’s shack could be reproduced and circulated by the image industry and was also a ready-made commodity fetish for the emerging hippie entrepreneurial reinvestment of drug money.

In a moving scene in Livin’ in the Mud, Helen Simpson confronts the North Shore contractors, who have come to bulldoze the Maplewood squatter homes.[26] “It’s not just us you are destroying,†she pleads, “it’s Nature.†I wonder if anyone would express themselves in such absolutist terms today. In this period, progressive consciousness was a collage that included more than just concern about the planet’s ecology, but a profound identiï¬cation with Nature as destiny. It was around such a notion that a ï¬ssure would appear in the art world between those, on the one hand, committed to ecological activism and who advocated or merely tolerated the increasingly problematic sentimental baggage that had built up around the establishment of Victorian and Edwardian decorative art as the template of organic, holistic aesthetics and those, on the other hand, openly committed to the urban situation and the discourses of international art and its burgeoning market. Underlying this ï¬ssure but not identical to it was another. The wholesale rejection of the idea of the artist and the autonomy of art had taken a very deep hold in Vancouver based on Situationist polemics. Artists such as Dean Ellis, Duane Lunden, and Dallas Selman, even as young luminaries, turned their backs on the practice of art, as surely as Rimbaud stopped writing poetry. Even those artists who continued to work had such an inured distaste for the institution of art that as they drifted away from its operations, they were forgotten. Others withdrew, making art very occasionally or not at all. But others, all of those featured in Intertidal, for example, re-engaged the historical problem of modernism and returned to the sanctuary of the autonomy of art. This distinction was given some authority by Jeff Wall, who, in 1990, theorized when responding in Rotterdam to Stan Douglas’ series of lectures on Vancouver art (held at the Western Front in 1990) with his own view of Vancouver art history: that art in Vancouver bifurcated at this time between “island†or “hippie†art and art that “prefers to concentrate on the conflict between the city and its natural setting.â€[27] But these distinctions are not so absolute that one artist could not embody both positions. An example of the ï¬ssure and the double embodiment would be Roy Kiyooka ’s reaction to Gary Lee-Nova’s artscanada piece, “Our Beautiful West Coast Thing.â€[28] Lee-Nova had proï¬led a handful of back-to-the-land artists rather than ones legitimized by the art world. Only one of them, Tom Burrows, had had recognition as an artist. As a rebuke, albeit a playful one, Roy Kiyooka took the magazine apart page by page and set it floating off a wilderness beach, documenting it as artscanada/afloat (1971). The piece both suggested the dangers of oblivion involved in retreating to the cabin in the woods and, as Kiyooka’s piece was itself then featured in artscanada, the sustainability of a self-referencing system of which art was the epitomic model.

The development of the arts during the sixties in Vancouver climaxed with the auto-da-fé of the Maplewood Mud Flats squat (December 18, 1971)—at least from the point of view of this paper. The period also marks several “passages†that are identiï¬ed with the sixties and that had an impact on Canadian identity or the lack thereof. Rather late in the day, but consistent with the independence movement throughout the former British Empire, Canada divested itself of the colonial identiï¬ers of Royal Crests and Red Ensigns. In 1965, the introduction of a new Canadian flag was the most conspicuous change in the semiotics of the state during this time. In the arts, it was a period of intense cultural nationalism centred in Ontario. Less tied to (and less cognizant of) this current of central Canadian nationalism, when freed of the British-based regionalism that had dominated art and writing through the 1950s, Vancouver artists turned international by engaging with the arts in California, London, and New York rather than Toronto. Vancouver artists did not cohere to the nationalist movement. In the years when “Canadian Literature†was crystallizing in Toronto, Vancouver poets joined the New American Poetry. While Ontario artists John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Weiland deployed Canadian icons and anti-American rhetoric, Vancouver artists entertained Dan Graham, Ray Johnson, Yvonne Ranier, and Robert Smithson. At the very time Canadian literature and art were consolidated in Eastern Canada, Vancouver went its own way to establish itself as a node in multiple international networks of poetry and art.

Originally published in Intertidal: Vancouver Art & Artists. Edited by Dieter Roelstraete and Scott Watson (Antwerp & Vancouver: Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen and the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, 2005, pp.30-49).

Footnotes

- 01. See Mudflats Living, a ï¬lm about the early 1970s counter-culture squats on the Maplewood Mud Flats in North Vancouver. Robert Fresco and Kris Paterson, Mudflats Living, 28 minutes, National Film Board of Canada, 1972. ↵

- 02. Research for the article was facilitated by a grant from the UBC Hampton Fund. Jesse Birch, Jessie Caryl, Lara Tomaszewska, and especially Séamus Kealy conducted the research and assisted with other aspects of the project. Thanks to Tom Burrows, Gerry Gilbert, René Poussin, Jamie Reid, and Gregg Simpson for providing ï¬rst-hand accounts of the period to the researchers and the author. ↵

- 03. As recently as 2004, Alan Elder wrote: “This was also a period when British Columbia, and particularly Vancouver, became a beacon of modernism in Canada . . . †in “The Artist, the Designer and the Manufacturer: Representing Disciplines,†A Modern Life: Art and Design in British Columbia, 1945-1960, ed. Alan Elder and Ian Thom, exh. cat. (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press and Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2004), 45. The idea that Vancouver in the Fifties was more modern than elsewhere was a ï¬ction resting on the published comments of two men: National Gallery of Canada Director, Alan Jarvis, and NGC Curator, Robert H. Hubbard. As a relative value judgment, it is not supportable unless you think Toronto’s Painters Eleven (1953) or Montréal’s Plasticiens (1955) less luminous than the Vancouver coterie. ↵

- 04. I remember that Andy Warhol ï¬lms were included among the projections. These projections took up a wall the entire length of the auditorium, making an environment that was not centred on the stage and the performances; one of the performances included that of the legendary Janis Joplin, who stood at the side, not the centre of the stage. ↵

- 05. Jamie Reid, e-mail correspondence with Séamus Kealy, 2005. ↵

- 06. The ï¬rst of these was the Marshall McLuhan-inspired lecture, The Medium is the Message, which was held at the University of British Columbia in 1965 and organized by a mixture of modernist and postmodernist artists and architects. The Sound Gallery/Motion Studio where Perry worked on modest light shows for performances of the Al Neil Trio was the bohemian laboratory for the Trips Festival. The Canada Council–funded Intermedia (1967-1971) represented another uneasy alliance between bourgeois and bohemian interests. Intermedia mounted sensorial events for the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1968, 1969, and 1970. After the collapse of Intermedia, the Vancouver Art Gallery continued to use the popular format with Paciï¬c Vibrations in 1973. See Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium is the Message,†Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (McGraw-Hill, 1964; reprint, with an introduction by Lewis H. Lapham, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1994). ↵

- 07. An account of James Tyhurst’s trial is found in Christopher Hyde, Abuse of Trust: The Career of Dr. James Tyhurst (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1991). Hyde presents circumstantial evidence that links Tyhurst to Ewen Cameron’s notorious CIA funded brainwashing experiments at the Allen Memorial Hospital in the 1950s. In addition, Hyde casts doubts on Tyhurst’s credentials. ↵

- 08. Dr. Paul Spong, founder of the Greenpeace “Save the Whales†campaign and denizen of the Maplewood Mud Flats squat, found this out when he was forcibly incarcerated by the same psychiatrist who had treated Perry. ↵

- 09. See “The Lost City: Vancouver Painting in the 1950s,†in A Modern Life: Art and Design in British Columbia, 1945-1960, ed. Alan Elder and Ian Thom, exh. cat. (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press and Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2004). ↵

- 10. Dennis Wheeler, “ The Limits of the Defeated Landscape: A Review of Four Artists,†artscanada (June, 1970), 51. Andrea Anderson, in her unpublished M.A. thesis on Tom Burrows, claims that Wheeler’s title was “corrected†by artscanada from the more dialectical “defeat(ur)ed.†Tom Burrows, “Sculpture of Concrete, Sculpture of Dreams†(Vancouver: unpublished, 1990). ↵

- 11. Ramirez was the wordsmith and singer for the rock group, the uj3rk5 (pronounced “you jerksâ€); the group included Kitty Byrne, Rodney Graham, Colin Grifï¬ths, Denise MacLeod, Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, and David Wisdom. ↵

- 12. Intermedia (1967-1976) was an artists’ collective devoted to exploring new media. It was born in scandal, as it received its ï¬rst Canada Council grant before it had incorporated, thus allowing a local paper to sensationally shout, “Non Existent Arts Organization Receives Government Funds.†Intermedia was housed in a three-story warehouse on Beatty Street (now a parking garage). In the early 1970s, Intermedia artists reached a large audience through a series of events staged at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Babyland was property acquired in Robert’s Creek, an hour outside of Vancouver. Babyland housed a pottery studio (Slug Pottery) and hosted performance events organized by Image Bank (Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov). ↵

- 13. Russian avant-garde scholar Ron Hunt taught at the University of British Columbia in the school year 1971/1972, and mounted a didactic show titled Poetry Must Be Made By All! Transform the World! at the Vancouver Art Gallery in July, 1970. ↵

- 14. Glenn Lewis’ performances were influenced by Deborah Hay and Yvonne Rainer. Hay was one of the founding members of the Judson Dance Theatre in New York, and is considered one of the most influential representatives of postmodern dance. She has collaborated with visual artists, composers, and choreographers, including Yvonne Rainer, among others. Yvonne Rainer is recognized as a dancer, choreographer, performer, ï¬lm-maker, and writer. She began choreographing in 1961, and made her ï¬rst ï¬lm in 1967. She is a key ï¬gure in the story of the New York avant-garde, in terms of both her writing and practice. ↵

- 15. From a letter written by Wallace to Dikeakos, Vancouver, March 1970, that was reproduced in an exhibition catalogue. See The Collage Show, exh. cat. (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Fine Arts Gallery, 1971), n.p. ↵

- 16. For information on Vancouver development, consult Donald Gutstein, Vancouver, Ltd. (Toronto: James Lorimer & Co., 1975). ↵

- 17. Vancouver was unusual in the amount of its downtown area—which is small and bound by the sea on three sides—owned by a few interests; chiefly the Canadian Paciï¬c Railway. Offshore, mainly American and British, interests owned signiï¬cant property in the city. These interests were not focused on building but in speculating on a future real estate boom. (Real estate prices were relatively stable between 1955 and 1964.) ↵

- 18. One thinks of Les Halles in Paris, the demolition of so much of old Montréal, and most of North America, the erection of curtain wall skyscrapers to house banks in every medium-size city on the continent. ↵

- 19. In the words of the late Kate Craig, one of the founders of the Western Front, “It was becoming increasingly difï¬cult to ï¬nd space to work . . . so when the Western Front building became available, we decided to buy it.†In Luke Rombout, Vancouver: Art and Artists, 1931-1983, exh. cat. (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983), 261. ↵

- 20. Peter Oberlander (Canadian/Austrian architect, city planner and author), and his former associate, Charles Stein (Head of the School of Community and Regional Planning, The University of British Columbia) were advocates of downtown development in Vancouver. Oberlander characterized the dwindling inventory of Edwardian buildings as “illiterate buildings†in an unpublished interview with me in 1983. ↵

- 21. Most notably, the city’s oldest neighbourhood, Strathcona, was saved from mass housing and freeways. A hotel was prevented from building at the entrance to Stanley Park, partly due to an almost year-long protest squat. Blundering and amateurism prevented other follies, such as a third crossing of Burrard Inlet. ↵

- 22. Sidney Hayer’s The Trap (1966) was earlier. ↵

- 23. Dennis Wheeler (Burrows’ friend) wrote his M.A. thesis on Malevich. Dennis Wheeler, Kasimir Malevich and Suprematism: art in the context of the revolution (master’s thesis, The University of British Columbia, 1971). ↵

- 24. Tom Burrows, “only take for granted the things you can touch,†artscanada 29:1 (February/March, 1972), 41-45. ↵

- 25. Tom Burrows also worked on the set of McCabe and Mrs. Miller. ↵

- 26. These ï¬lms were both largely completed when the city torched Burrows’ house, so the viewer would not know that some squatters stayed. The issue resurfaced in 1973 and again in the mid-1980s as “Old Mike†(Mike Bozzer) had been allowed to stay in his squat, but eventually left to enter a nursing home and his house was occupied by a squat activist. ↵

- 27. Jeff Wall, “Four Essays on Ken Lum,†Ken Lum, exh. cat. (Rotterdam: Witte de With and Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1990), 39. ↵

- 28. Gary Lee-Nova, “Our Beautiful West Coast Thing,†artscanada 28:3 (June/July, 1971), 22-38. ↵

Author Bio

Scott Watson

Curator, writer, art historian, educator. Scott Watson is a Professor in the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory and Director/Curator of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia, where he is also Chair of the graduate Critical Curatorial Studies program. He has published an award-winning book on Canadian artist Jack Shadbolt (1994) and a monograph on Stan Douglas (1996), as well as many articles and catalogue essays on postwar and contemporary art. Watson’s research focus is contemporary art and issues, art theory and criticism, twentieth century art history, and curatorial and exhibition studies. He is currently researching Concrete Poetry for an upcoming publication and exhibition, and editing a book on British Columbia’s studio pottery movement.

Related Items

- 01. A Portfolio of Piles

Ingrid Baxter (Ephemera) - 02. WECO dancers performing at the Motion Studio

Jack Dale (Photograph) - 03. Participant dancing in front of the bandstand at the Trips Festival

Jack Dale (Photograph) - 04. La Melancolie de la Rue

Ian Wallace (Photograph) - 05. WECO dancers performing at the Motion Studio, Karen Jamieson pictured at right

Karen Jamieson (Photograph) - 06. Dancer Heather McCallum performing at the Motion Studio

Jack Dale (Photograph) - 07. WECO dancer Heather McCallum performing at the Motion Studio

Heather McCallum (Photograph) - 08. Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A Fragment of a Greater Fragment (catalogue cover)

Grant Arnold (Book) - 09. Audience member at the Motion Studio

Jack Dale (Photograph) - 10. Glue Pour

Robert Smithson (Photograph)

Project Sites

Discrete project sites documenting the work of specific artists and collectives in detail.

- 01Aboriginal Art in the Sixties

Curated by Marcia Crosby

Research by Roberta Kremer Designed by The Future - 02Al Neil

Curated by Glenn Alteen Designed by Archer Pechawis - 03Expanded Literary Practices

Curated by Charo Neville

and Michael Turner Designed by The Future - 04The Intermedia Catalogue

Created by Michael de Courcy

Research by Sarah Todd Designed by James Szuszkiewicz - 05Transmission Difficulties

Curated by Scott Watson Designed by Dexter Sinister

- 01Aboriginal Art in the Sixties

Essays

Essays and conversation providing a context for exploring the Project Sites and Archives.

- 01Making Indian Art “Modern”

By Marcia Crosby - 02Vancouver Cinema in the Sixties

By Zoë Druick - 03UBC in the Sixties: A Conversation

Edited by Marian Penner Bancroft - 04Siting the Banal: The Expanded Landscapes of the N.E. Thing Co.

By Nancy Shaw - 05Urban Renewal: Ghost Traps, Collage, Condos, and Squats

By Scott Watson

- 01Making Indian Art “Modern”

Video Interviews

Video interviews conducted between December 2008 and May 2009 reflecting on Vancouver’s art scene in the sixties.

- 01Ingrid Baxter with Grant Arnold

- 02Christos Dikeakos with Lorna Brown

- 03Carole Itter with Lorna Brown

- 04Gary Lee-Nova with Scott Watson