Essays / Nancy Shaw

Siting the Banal: The Expanded Landscapes of the N.E. Thing Co.

Download PDFThe concept of everydayness does not therefore designate a system, but rather a denominator common to existing systems including judicial, contractual, pedagogical, fiscal, and police systems. Banality? Why should the study of the banal itself be banal? Are not the surreal, the extraordinary, the surprising, even the magical, also part of the real? Why wouldn’t the concept of everydayness reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary?

—Henri Lefebvre

By making life more interesting for others, we may indirectly help to alleviate the human condition. We up your aesthetic quality of life, we up your creativity. We celebrate the ordinary.

—N.E. Thing Company

“To change life-style,†“to change society,†these phrases mean nothing if there is no production of an appropriated space.

—Henri Lefebvre

Throughout their collaboration (1966–1978), Iain and Ingrid Baxter utilized the N.E. Thing Company—their incorporated business and artistic moniker—as a vehicle through which to investigate artistic, domestic and corporate systems in relation to their everyday life. Like typical West Coast and Canadian artists, the Baxters made landscapes, though theirs were expanded to include the sites of work and leisure, and urban and suburban spaces. They were uninterested in painting pictures of Canadian wilderness as a hostile, unexplored territory full of myth, mystery or awe-striking grandeur—all that is other to the obvious and banal spaces of the everyday. Instead the Company’s landscapes investigated how information technologies, corporate relations and institutions such as the art world and the nuclear family interact to redefine “landscape” as a product of human interest, an element of subjectivity and charted its relationship to forms of identity and national positioning. NETCO’s reversals, reflections, inflatables, mappings, punnings, and measurements, disrupted unidimensional, unidirectional hegemonic annexations of space. The Company actively appropriated and transformed these spaces to allow for creative possibilities and critical potential. At the same time as the Baxters’ landscapes attempt to map out a coherent picture of fragmented realms, in a move that is characteristic of the contradictions explored in their work, these landscapes stake out a social topography in the emerging, geo-politically peripheral city of Vancouver in the late sixties.

Although the Baxters were contemporaries of the Situationists (who were among the first to incorporate Henri Lefebvre’s analysis of everyday life into their practice), it is necessary to distinguish NETCO from its French counterparts. Lefebvre and the Situationists saw everyday life as a site of revolutionary potential to be liberated through aggressive reversals and combative tactics of negation—a space from which to undermine the corporate state through dialectical analysis of and critical intervention in consumer society that revealed the stakes capital has in maintaining a separation between the realms of work and leisure, the political and the everyday.[1] Although the Baxters attempted to integrate the spheres of work and leisure, they aimed to open potential spaces of creativity within existing economic and political constraints by breaking down habitually assumed modes of perception in order to up the quality of life—a life that took account of family, business, and art activities. The Baxters proposed an agency that was expansive, inclusive and celebratory in place of the Situationist’s disruptive and radically motivated interventions. They playfully questioned their roles as entrepreneurs, artists, educators, parents and spouses, collapsing and infecting systemic boundaries in order to reinvestigate the elusive and taken-for-granted.

The Baxters were ambivalent about their roles as artists – they viewed art as only one of several means through which to explore their ecological and educational interests. By investigating these interests within systems of meaning, they hoped to set an example for others by creating an integrated life for themselves. Not surprisingly, the Baxters did not enter the art world through the standard art college route. The two met at Washington State University in Pullman. Ingrid studied music, recreation and education while Iain studied biology and zoology and enjoyed wildlife illustration. After Iain obtained a MFA, he began investigating contemporary materials and methods of object-making, expanding upon modernist conventions.[2] His bagged and vacuum-formed landscapes were significant early work which employed up-to-date industrial techniques such as heat sealing and moulding: the idea of bagging played on consumer packaging as well as hunting pr¬ocedures. The landscapes were stylized and toylike, captured and preserved in the most modern of materials – plastic. Mixing and matching the materials and motifs of consumer culture, this work enlisted Pop Art strategies and highlighted links between fine art, consumer durables, industrial processes and advertising techniques.

While incorporating Pop Art procedures, NETCO produced landscapes that provided innovative images of a West Coast lifestyle mimicking notions of leisure and industry promoted by the likes of Beautiful British Columbia—a government-sponsored magazine fashioned after National Geographic which painted a picture of B.C. and Vancouver as a natural resource and recreational wonderland. In the late sixties Vancouver was changing from a frontier town and colonial outpost—appropriately known as Terminal City—to a growing metropolis reflective of B.C.’s booming resource-based economy. It acquired a dual identity represented on the one hand by young executives and on the other by disaffected groups. A new breed of upwardly mobile executives emerged to promote and support the development of primary industry and urban growth. In some senses, the maverick traders, the penny stocks and fly-by-night operations of the Vancouver Stock Exchange exemplified the city as a corporate frontier. The scenery and leisure activities afforded by Vancouver’s natural splendour was an added bonus for such up-and-coming executives who could boat, ski and golf year round. As well as a port city and the western periphery, Vancouver attracted a conglomeration of misfits looking for a better life, among them hippies and American draft dodgers. Although outdoor recreation took precedence over the arts, alternative sensibilities in one way or another challenged prevailing, parochial and colonial, and genteel modernist traditions.

The Baxters were not a typical family—they actively participated in Vancouver’s flourishing interdisciplinary, counter-cultural and avant garde art scene in the late sixties. Perhaps their domestic, artistic and company headquarters in the wooded suburbs of North Vancouver, just past the Second Narrows Bridge—a location midway between the more affluent suburbs of the North Shore and the reprieve for transient and counter—cultural elements, the Dollarton Mud Flats and Deep Cove—literally locates the Baxters’ position. Their home, starting as a small cottage, eventually resembled a hybrid v¬ersion of West Coast architecture. The typical homes used post and beam construction based on modernist architectural principles where clean, functional spaces mixed with commanding views to create a safe and clean environment with an abundance of fresh air and recreation—a well-deserved tonic after the malaise and confusion of the modern work-a-day world.[3] The Baxters disrupted this suburban pastoral by using the family abode as company headquarters and artistic playground for the business of living and working rather than contemplative escape and repose. Their dwelling was in a state of constant transformation, whether in the form of ongoing additions to the house or in its use as living space, studio and office. The Baxters treated their home, which they called the Seymour (see more)[4] Plant, as a sculptural assemblage; adding elements of industrial, recreational and commercial architecture—a corrugated tin roof used on barns, large wooden floor planks from a warehouse, a section of a supermarket awning over the deck doors, and a prefab, built-in, vacuum-formed pool in the front yard. The spectacular view enjoyed by more affluent neighbouring suburbs was replaced with the Baxters’ working vista—a large back yard—framed with trees and edged by the Seymour River. They hosted parties and studio visits: many local and international artists, curators, funding officials and critics attended for fun and the often heated debate that took place at social gatherings on a regular basis. Regardless of the Baxters’ investments in the ideals of corporate, family and suburban life, they transformed the rigid boundaries of this life to accommodate artistic possibilities. And, unlike most nuclear families, they paid attention to the link between making a living, art-making and the domestic and social base that is integral to such production.

As well as facilitating this interface between the art world and the suburbs, they further traversed conventional boundaries by making art in their yard and using their yard as aesthetic landscape. Much of their yard work involved puns on and experiments with conventions of image-making and measurement. For example, Single Light Cast (1968) and Double Light Cast (1968) were about light and angles of reflection. In each work mirrors were placed in the river and photos were taken at different angles and distances: the intent was to provide a comparison of how mirrors and water interact to create an image of light, and to show how this light is recorded by the camera. Reflected Landscape (1968) also employed a mirror-piece in water, but this time the mirror reflected the tree tops and sky, providing a picture within a picture: this included what would otherwise be outside the photographic frame while, at the same time, deferring and deflecting perspectival recession to frustrate easy visual movement through the pictured landscape. In VSI Formula #5 (1969) algebraic formulas determine the location and angles of mirrors placed in grass, trees and the river to reflect water, sky, land and the house. The equations mimic systematic codification; however the formulations are arbitrary and unresolved. The attempt to represent the unrepresentable in Approx. 2,500,000 Gallons of Water (1967) was another form of measurement. The object of this experiment was to record the movement of water through time and space without photographing the same section of water twice. Photographs were taken from one position at twenty-second intervals—the time it took for a piece of wood to travel in the water through the picture frame. An engineer’s calculations then determined the volume and speed of the water as it was recorded by a 35mm camera. Mounted in a grid, the resulting frames gave a sense of the water’s movement using the illusion of cinematic sequence.[6]

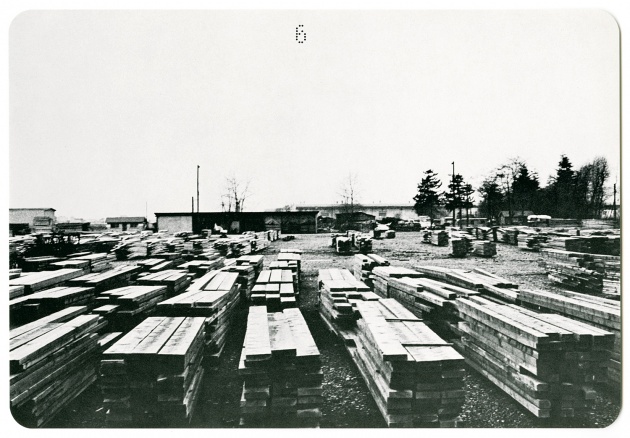

Beyond the family property, their explorations extended through the urban and suburban landscape on Sunday drives with kids, dog and whoever else was available. Favourite destinations included flea markets, second-hand hand stores and dumps; the members of the Company collected used and castaway objects to be employed in a variety of artistic and domestic purposes, as well as objects to be claimed and enjoyed. On many of these excursions, rather than going to typical sightseeing and leisure destinations such as shopping malls, amusement parks, scenic viewpoints, or affluent neighbourhoods, they visited unlikely places such as the industrial waterfront. Their tours resembled a suburban version of a Situationist derive, bringing attention to the hidden and productive spaces of capital in the city — usually the places avoided during family leisure time. These spaces were documented in the Portfolio of Piles (1968) when the Company went around the city photographing found piles of sulfur, lumber etc. In an exhibition of Piles at UBC (1968), the Baxters also displayed piles of things such as hair, eggshells and tin cans.[7] The Piles punned on formalist aesthetics concerned with abstract notions about structure and composition which were considered to be the essence of high modernist aesthetics. NETCO’s Piles were of found things that were necessary to the business of living—the primary resources necessary to facilitate, or the by-products of production, accumulation, use and exchange. Their Piles displace the rarified and isolated realm of aesthetic contemplation with the detritus of everyday life.

The Sunday drive as a form of touring the city was continued in method and production values in the ACTs (Aesthetically Claimed Things) because the pictures resembled family snapshots often taken from the vantage point of a car window. The ACTs were a series of black and white photographs stamped with the Company seal and assigned numbers and titles denoting location and significance, recording, among other things, innovative and intriguing forms throughout the city. Their claims acted as reminders that art was already all around in the built environment—it wasn’t exclusively for galleries and museums. The Baxters’ personal taste revolved around modern, especially minimal forms: in functional structures such as the guard railings leading to a family bungalow in ACT #128: Entrance Railings, North Vancouver, 1968 and as emblemata and entrance decoration in ACT #25: Three Orange Columns, Fairfield and Hartford Place, Seymour Heights, North Vancouver, 1968 illustrating three posts marking the opening boundaries of a developer’s suburban venture. ACT#40: MacMillan Bloedel Building, Corner of Thurlow and Georgia, 1968 documents Arthur Erickson’s concrete modernist headquarters built for the local forestry moguls, providing a unique example of West Coast corporate architecture. Unlike the typical glass curtain wall of most modern of¬fice buildings, the mass brutalist structure was made of concrete which Erickson considered a modern equivalent to marble — because of its strength and durability and ability to change in tone according to the weather and time. This minimal and commanding form at once blended in with, while dominating, the earthy splendour of Vancouver. In order to foreground the banal, functional aesthetics found in the architecture of urban infrastructure the Company claimed a retaining wall in ACT #55: Cement Barrier, Seymour Parkway, North Vancouver, 1968. In ACT #30: Cement Transitional Wall Along Park and Tillford Co. Main Street, North Vancouver, 1968, the object of interest was the wall marking the boundary between the public space of a major thoroughfare and the corporate space of the Park and Tillford gardens and distillery. The Baxters were also fascinated by signs, especially those that everyone immediately recognizes, such as company logos claimed in ACT #36: Safeway Store Ltd. Symbol, North America, 1968 and directional signs claimed in ACT #130: Big Arrow, Park Royal Shopping Mall, 1968 and ACT #58: Get It at Woodward’s Garage, Free Parking and Two Arrows Woodward’s Shopping’ Centre, Cambie and Cordova, 1967. Even though they were claimed for other intentions, the ACTs discussed in this section leave a record of several civic landmarks that were built by local family businesses to announce their economic strength and business savvy. Today, the Baxters’ ACTs have become quirky historical records because these businesses have fallen on hard economic times, leaving the landmarks as testaments to former power.[9]

Although NETCO production values varied, new imaging technologies enhanced the Company’s depiction of the urban landsc¬ape. For one body of work NETCO made back-lit Cibachrome images, then a new, high-resolution photographic material:[10] presented as a transparency and illuminated by fluorescent lighting, these images greatly enhanced specular illusion, providing an improved form of billboard advertising. The use of this new technology was suited to the urban environment built in part to facilitate the smooth and unfettered flow of capital accumulation through financial, administrative, transport and information networks, always subordinating history and difference to abstract and generalized space.[11]

The N.E. Thing Company filled its Cibachrome signs with images of habitation and detritus; with the nonproductive spaces that bear the traces of an everyday space that is dynamic and heterogeneous. Their Cibachromes featured such things as the underside of a bridge (Connection, 1968) and a gravel pit (Final, 1968).[12] A hillside of detached homes titled Ruins (1968) juxtaposes notions of suburban living space with remains of obliterated civilizations and history. In another move, the Baxters appropriated leisure industry landscapes as mementos of family outings. In Shift (1968) they took a picture of an image of a sunset used, on a B.C. Ferry, to promote the splendour of the province’s landscape. Reflected in the Baxters’ picture is the inside of the ferry. Landscape (1968) features one of the drive-in menus, complete with a panoramic landscape that families enjoyed while eating at White Spot Restaurants. The White Spot was of course the perfect place to end up on a Sunday drive.

As an extension of their city tours, the Baxters took auto-vacations through Canada and the United States, making work on the way to exhibitions in other cities. Their most ambitious travelling project was the unrealized 5,000 Mile Movie (1967) conceived to capture Canada, coast to coast via the Trans-Canada Highway. Due to the scale and expense of the project, only a four-mile section was completed. But in the style of actual movie producers, the Company always promoted and attempted to raise funds for the project.[13] While the 5,000 Mile Movie posed as a documentary record of the Baxters’ trip across Canada, it made an analogy between the position of film viewers and car riders as detached spectators who experience space in linear progression and in predominantly visual terms.[14]

While attempting to represent the extent of the country in as literal a fashion as possible, the work’s course—the Trans-Canada Highway—would have documented one of Canada’s mythic transportation networks, perhaps second only to the railroad in the effect it had for the modernization and industrialization of Canada. The Trans-Canada is one in a network of highways that proliferated throughout North America, especially after WW II, to facilitate economic development by serving as conduits moving primary resources to manufacturing centres in Central Canada and the United States. For the tourist industry, scenic routes were built for vacationers. In B.C., highway construction was carried out in maniacal proportions under the then Social Credit government’s Minister of Highways, Flying Phil Galardi. As well as constituting a means of modernization through which to exploit and harness B.C.’s landscape for industry and tourism, highway building was in part a political payoff—linking Vancouver to inland cities in the Caribou and Okanagan, the bastions of Social Credit support.

Depending on the purpose, highways either subordinate or construct experiences of landscape; calibrating devices include signage, lookouts, historical sites, campgrounds, service stations, rest stops, motels, etc.[15] In 1/4 Mile Landscape (1968), made for an exhibition in Newport Beach, California, the Baxters called attention to highway landscape by placing three roadside signs—You Will Soon Pass By a 1/4 Mile N.E. Thing Company Landscape, Start Viewing and Stop Viewing—across claimed territory. Another version of the piece was made for Prince Edward Island (1969) where the company received inquiries from interested real estate buyers.[16] The 1/4 Mile Landscape appropriated the highway vista as corporate and aesthetic property while bringing attention to the construction of landscape as object of aesthetic enjoyment by a transient car viewer.

On another family trip, received patterns of directionality were reversed when the Baxters travelled from North Vancouver to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (1969) to set up shop for an exhibition. They annexed the first floor of the gallery for Company headquarters, displayed and demonstrated their company wares, and offered their services as visual consultants. The set-up was so convincing that one passer-by stopped to ask the rental cost of such a prime location. There to open the NGC’s first environment was Ron Basford, the Minister of Consumer and Corporate Affairs, who praised the company for its innovative and industrious artistry.[17] The presence of the exhibition, while announcing the N.E. Thing Company to the nation’s capital, ironically commented on cultural policy. Federal cultural policy had always been indirectly concerned with national identity, especially with the formation of the Canada Council in 1957 established to foster and support the arts. However, by the late sixties, culture had become more politically instrumental and policy was initiated for the central administration and dissemination of official culture to be developed by national institutions in Ontario and Quebec and deployed through touring and regional development programs.[18] NETCO reversed the trend by literally transporting its cultural production to Ottawa, ingratiating and impressing itself upon centrally placed administrative officials and systems with its self-starting attitudes and inventive merchandise.

In similar fashion, a transformative dynamic was unleashed in other Company environments such as the post and lintel structure built at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery in 1969. The common housing construction structure infused the commercial gallery with a domestic and minimalist aesthetic involved in the production of standardized, mass- produced objects, spaces and environments. Moreover, the Company’s first environment, Bagged Place, built in the UBC Fine Arts Gallery in 1966, inhabited the gallery space with the makings of a four-room apartment with everything covered in plastic. In these and many other environments, the Baxters infused art spaces with domestic and corporate structures, naturalizing their hybrid inhabitation while questioning what had been previously naturalized.

To compliment their travel activities, the Baxters planned, and in a few instances executed, environmental ¬artworks mimicking industrial installations. In a sense, by placing vacation and industrial activities in complementary positions, the Company accentuated the links between labour and leisure obscured in official propaganda. The B.C. government aggressively promoted its industrial resource base while presenting the province as an edenic, exotic and fantastically varied vacation wonderland—a get-away for the agents of resource exploitation. Official promotion always obscured the fact that the so-called modernization of B.C.’s landscape through tourism and industrialization shaped frontiers for money making. The N.E. Thing Company imitated official promotion, but the playful and benevolent gestures were concerned with ecological and artistic dynamics rather than with the extraction of surplus value. The company proposed to make White Vinyl Snow Cap for a Mountain Top (1966), a plastic snow cap design for a barren mountain peak. For Chrome Poles Move (1966/68) plans were made to place chrome poles in the Athabasca Glacier to mark the ice’s natural movement, leaving the poles to drop a sculptural record of the glacier’s recession. NETCO’s hydro projects consisted of releasing objects and dyes in water to observe the force and energy of water movements. For the Nevada desert, the Baxters wanted to stage a snow storm whereby snow configurations would be retained after the thaw by inset cooling coils.[19] Furthermore, they photographically documented examples of industrial architecture in ACTs such as ACT #7: Snowshed Tunnels 30 Miles East of Salmon Arm, 1967 and ACT #10: Power Poles and Clearing, Trail B.C., 1968. These ACTs were framed to reflect the minimal structures of industrial architecture and production – function and structures taken up by minimalist aesthetics — that are coterminous with instrumental and standardizing tendencies of industrial production processes.

In addition to proposing environmental works and claiming industrial architecture for the aesthetic record and vacation memories, NETCO incorporated concepts of the North and snow as spatial motifs associated with myths about Canadian landscape. For the Baxters, snow doubled as a blank page or canvas to be shaped and moulded. Iain made snow drawings while skiing, using his body as drawing implement and snow as support. Drawings such as One Mile Ski Track (1968) and Converging Drawing (1968) were carried out on Mount Seymour, the neighbourhood ski slope. In Snow (1968), the substance was brought to the gallery by placing a photograph of it on the floor covered with bullet-proof glass for patrons to walk over. And, in P-Line Straight (1968), drawings were made by peeing in the snow, evoking infinite jokes about the staking out of artistic and spatial territory and, by extension, the forging of industrial frontiers. These drawings were small, personal gestures that on an everyday scale made fun of the grandeur and more instrumental process involved in shaping the land for exploits of tourism and industry.

To further its investigation of Northern motifs, the Company travelled with Lucy Lippard and Lawrence Weiner to Inuvik, N.W.T to make works for a show organized by Bill Kirby at the Edmonton Art Gallery.[20] The Baxters explored mythic notions of the Arctic as a barren, unexplored wilderness, unpopulated, open and infinite, subject to the extremes of daylight and dark night. While carrying out Company work, NETCO implicitly acknowledged—through the making of maps and the claiming of landscapes—that conceptions of the North as an unpopulated wilderness overshadows and inadvertently legitimizes exploitation of the North as one of the last industrial frontiers.[21]

As a means of recording their explorations while making artistic and personal, everyday alternatives to the rationalized grid of land surveys and maps, the Baxters undertook mapping projects on their expeditions in and around Inuvik. Most maps are made to identify geographical terrain and settlements and to facilitate travel by presenting an abstract, instrumental image of the land with knowledge necessary for extraction, production, distribution and accumulation. Although the Baxters mimicked the conventions of mapmaking, their maps were composed of gestures that made navigational marks on the landscape, documenting space they actually traversed, and through performances, exploring concepts of directionality. In Black Arctic Circle (1968), NETCO planned to transpose mapping notations onto the landscape. For the piece, a low-flying jet would release black dye at one-minute intervals—laying down the Arctic Circle as it appears on maps. By transcribing systems of mapping onto the actual landscape, the Company enacted a reversal, revealing the arbitrary and calculated nature of cartography while claiming the landscape as a work of Company art.

As urban and corporate explorers, the Baxters set out on many sightseeing expeditions. In Circular Walk Inside the Arctic Circle Around Inuvik, NWT (1969) the Company presidents wore pedometers to scientifically mark the seven km or 10,314 steps travelled around the circumference of Inuvik. They documented 16 Compass Points Inside the Arctic Circle (1969), and Lucy Lippard Walking Toward True North (1969) through a quarter mile of tundra. In these and other pieces they literally performed, in banal acts, the abstract and totalizing concepts of directionality. Territorial Claim (1969) inside the Arctic Circle was dedicated to Farley Mowat and his book about the North, Never Cry Wolf, a Canadian classic. The narrative explores the existential and physical machinations and rites of passage involved in eking out boundaries that differentiate between the self and extremes of nature. As an extension of P-Line Straight—from North Vancouver to the Arctic—Iain made his personal artistic mark by pissing in the snow. He planned to make this decisive gesture time and time again in other significant locales thereby “marking his personal life-time in territorial space.[22] Pissing was considered a transgressive act, illegitimate artistic medium and polluting gesture. When the piss work is considered in relation to plans for ecological pieces, such as the dye drops and “earthworks,†it becomes clear that the Baxters were interested in an ecology of space, time and viewing processes rather than with environmentalist concerns for preserving nature as a wilderness free of unfriendly human presence. The Company’s plans for sculptures and markings assumed free range in annexing landscape and if the projects were realized they might have met the same fate as Robert Smithson’s proposed Glass Island in 1970 on one of the Gulf Islands which was cancelled because environmentalists felt that the project would cause permanent and irreparable damage.

The Arctic work, as well as other landscape pieces, were accompanied by standard road and geographical maps that the Baxters marked with instructions and drawings. In doing so they transformed official maps from representations of regulated and unidimensional space into dynamic and contingent space. By inflecting mapmaking practice with their actual experience of and activities in Inuvik, the Baxters transformed abstract and instrumentalizing concepts into the realm of the everyday, disrupting the objectivity of the rationalized grid that presupposes a homogeneous subject, and a static space that ignores time and history.

Reflected Arctic Landscape (1969) was another joke on transparency and objectivity in picture making. Masquerading as a typical picture postcard, the piece set out to capture an Arctic sunset by taking a photograph of it as it was reflected in a mirror placed on the ground. The resulting image was presented as a back-lit transparency—illuminating a constructed image reflecting and refracting the sun, demonstrating the difficulty for and limitations of photograph, in simultaneously capturing the sunset and landscape due to intense and extreme lighting conditions. Reflected Arctic Landscape was eventually published in Peter Mellon’s coffee table book, Master Works of Canadian Art. While presenting itself as a typical Canadian landscape recording the grandeur, extremes and impossibility of this landscape, they foregrounded technical finesse and pictorial construction humourously quoting the artifice involved in making such pictures.

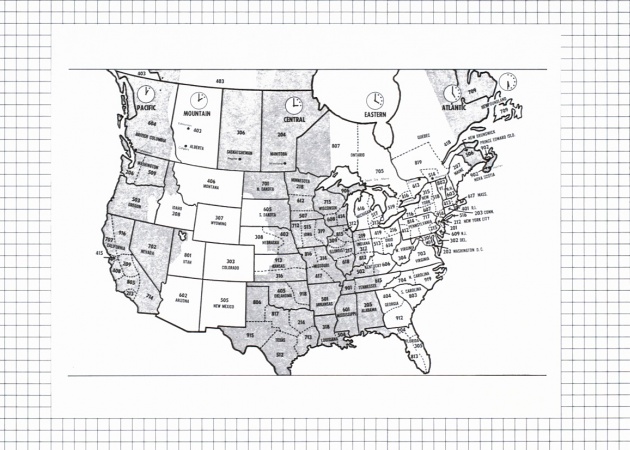

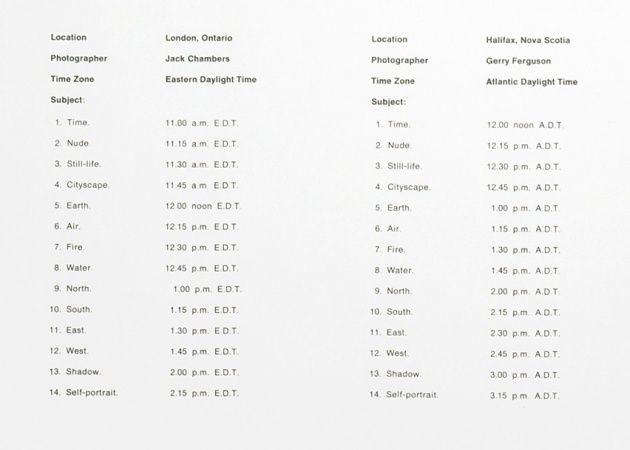

As tourists, cartographers and artistic investigators, the Baxters carried out Company activities by dispatching NETCO communications such as the Telexed Triangle (1969): the transmission spanned from Inuvik to Halifax to Vancouver, using a geometrical form to illustrate spatial concepts constructed by electronic communication. This challenged existent perceptions of time and space by conflating the two to create a sense of simultaneity and the projection of geographical homogeneity. Telexes were also sent to classes at Nova Scotia School of Art and Design instructing students to make art.[23] In this and other work, the Baxters were influenced by Marshall McLuhan. According to McLuhan, artists were early warning systems who perceived shifts in sensory perception effected by technological change. In what McLuhan called the Global Village, a shift was taking place from print technology that favoured visual and linear perception, to electronic and communications media that employed all the senses and favoured simultaneity. In the Company’s interpretation of McLuhan, communications media were used to an advantage by sending telex and telecopier messages from geographic, political and economic peripheries, creating what Ingrid called an aesthetic of distance[24]—a means through which the Company could traverse time and space, inserting its presence in territories that it would otherwise be excluded from. As with McLuhan, the Baxters saw themselves as probes—eclectic and eccentric—asking the types of questions that would lead to the collapse of established and official boundaries, setting the groundwork for, and encouraging and advising others to continue with, systematic and scientific studies. Furthermore, communication works were also a cheap, easy, quick and portable means of artistic demonstration which allowed for an infiltration of national and international corporate and artistic systems that traverse geo-political boundaries.

The Baxters’ hybrid sensibilities were evident in their landscape investigations: those investigations encompassed anything, including nature, mapping, environmental and communication systems, the body, the suburban and urban. Their work resided within the gaps and boundaries of established systems that foregrounded the banal and taken-for-granted. The Company poked gentle fun at existing boundaries in order to improve the quality of life for themselves and others while inadvertently leaving a partial social document of their hybrid and polymorphic milieu. Through wit and play they appropriated established and rigidified conceptions of landscape to reread it as constellations of collapsing and interacting territories, calling attention to the hidden interdependence of corporate, artistic and domestic spheres. The agency required to redefine these boundaries was transformative, hinting at possibilities for other kinds of intervention.

Originally published in You Are Now in the Middle of a N.E. Thing Co. Landscape, Feb. 19 – Mar. 27, 1993 (Vancouver: UBC Fine Arts Gallery, 1993).

Footnotes

- 01. For a discussion of everyday life see Henri Lefebvre, Everyday Life in the Modern World (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1984) and Guy Debord, “Perspectives for Conscious Alterations in Everyday Life,” Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981):68–75. ↵

- 02. Marie Fleming, Baxter2; Any Choice Works (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1982):10–11. ↵

- 03. Scott Watson, “Art in the Fifties: Design, Leisure and Painting in the Age of Anxiety,” Vancouver Art and Artists 1931–83 (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983): 77 for an analysis of modernist artists, architects and patrons who were committed to such utopian ideals of suburban living in the 1950s. ↵

- 04. Marie Fleming, 29. ↵

- 05. Unless otherwise noted, all information is from conversations with Ingrid and Iain Baxter in 1992. ↵

- 06. See Marie Fleming, 48 for a more thorough description of the yard and mirror works. ↵

- 07. Portfolio of Piles was presented as a series of black and white postcard-like images. At the UBC Fine Arts Gallery, exhibition visitors were given a map and were expected to travel around the city to view the Company’s found piles. ↵

- 08. NETCO also made ARTs (Aesthetically Rejected Things) and proposed to make ANTs (Aesthetically Neutral Things). ↵

- 09. For example, the Woodwards, one of Vancouver’s important entrepreneurial families, started a dry goods store at the turn of the century which eventually developed into a chain of B.C.-based department stores. Significantly, the Woodwards were involved in building Oakridge Centre (one of the first shopping malls built in Canada) and Park Royal in West Vancouver, which at the time of its opening was the largest covered shopping mall in North America. Over the past few years the local tycoons have fallen into economic difficulties. Park and Tillford is now a shopping mall and multimillion dollar movie production studio. Woodward’s Food Floor was sold to Safeway and the company is trying to avoid bankruptcy by vacating its downtown store pictured in ACT #58. MacMillan Bloedel sold its building and the company is currently owned by Cominco, a division of Canadian Pacific Investments. ↵

- 10. One of NETCO’s commercial ventures was a Cibachrome lab opened in 1974, the first west of Toronto. ↵

- 11. Henri Lefebvre, “Space, Product and Use Value,†Critical Sociology: European Perspectives, ed. J.W. Freiberg (New York, 1979): 289–90. ↵

- 12. The photographs were taken in 1968 and shown at Carmen Lamanna Gallery in 1969. ↵

- 13. NETCO first proposed the movie for an exhibit at the Osaka Expo ‘70. In 1973, they attempted to get funding from the provincial government who would then give the movie as a gift commemorative of B.C.’s centennial to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. An American cigarette company offered to sponsor the movie; however the corporation stipulated that it had to be shot documenting a trip that took place along the American-Canadian border which, of course, would ruin the whole idea of the trip. The movie is still a possibility and may one day be completed with video. ↵

- 14. Alexander Wilson, The Culture of Nature: North American Landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez (Toronto, Between the Lines, 1991): 34. ↵

- 15. Alexander Wilson, p.19–51 for a discussion of highway landscape. ↵

- 16. The most recent 1/4 Mile Landscape is located on Chancellor Boulevard for the duration of this exhibition. ↵

- 17. Marie Fleming; p.82. ↵

- 18. For an analysis of the centralization of Canadian culture see Dot Tuer, “The Art of Nation Building: Constructing a ‘Cultural Identity’ for Post War Canada,” Parallelogramme (March, 1992): 24–37 and David Howard, “Progress In the Age of Rigormortis” (unpublished MA Thesis, UBC, 1986). ↵

- 19. For a more complete listing of the Baxters’ unrealized projects see Lucy Lippard, “Iain Baxter: New Spaces,” artscanada (#2–33, June 1969), 7 and Report on the Activities of the N.E. Thing Company Limited at the National Gallery of Canada 4 June–6 July 1969 (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1969), unpaginated. ↵

- 20. Lucy R. Lippard, “Art Within the Arctic Circle,” The Hudson Review (Feb, 1970): 666–674. ↵

- 21. Alexander Wilson, p.282–289, for a discussion of competing ideological conceptions of Northern landscape. ↵

- 22. The N.E. Thing Co. Ltd. Book (Vancouver and Basel: NETCO and the Kunsthalle Basel, 1978), unpaginated. ↵

- 23. Trans-VSI Connection NSCAD-NETCO Sept. 15–Oct. 5, 1969 (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1970). ↵

- 24. Anne Rosenberg, “N.E. Thing Company Section: Interview,” The Capilano Review (no. 8/9, Fall 1976/Spring 1976): 178. ↵

Author Bio

Nancy Shaw

Writer, critic, curator, educator. Nancy Shaw was an award-winning poet, scholar, art critic, and curator. Author of Affordable Tedium (1991), and Scoptocratic (1992), Shaw frequently collaborated with poet Catriona Strang. They co-authored Busted (2001) and Cold Trip (2006), and their collaborative work was published in Big Allis and Raddle Moon. Shaw received a Doctorate of Philosophy in Communications from McGill University in 2000 and held a post-doctoral fellowship at New York University. Her doctoral dissertation, “Modern Art, Media Pedagogy, Cultural Citizenship: The Museum Of Modern Art’s Television Project, 1952-1955,” was judged as a superior work. Just prior to her death in 2007, she was engaged in new research on McLuhan and the visual arts. During the 1980s in Vancouver, she was at the centre of interdisciplinary collaborations, contributing as a writer, artist, curator, and critic. This vibrant period spawned artist- and writer-driven initiatives in Vancouver such as the Or Gallery, the Kootenay School of Writing, and Artspeak Gallery, to which she contributed in formative ways. During her career, Shaw taught at McGill University, Rutgers, Simon Fraser University, and Capilano College.

Related Items

- 01. P + L + P + L = VSI

N.E. Thing Co. Ltd (Print) - 02. Act # 110 - Statuary Shop Corner of Marine Drive and Pemberton, North Vancouver, B.C., 1968

N.E. Thing Co. Ltd (Collage) - 03. BC Almanac: N.E. Thing Co. Ltd

Ingrid Baxter (Book) - 04. Snow

Ingrid Baxter (Photograph) - 05. BC Almanac: N.E. Thing Co. Ltd

N.E. Thing Co. Ltd (Book) - 06. Lucy Lippard Walking Towards True North

Iain Baxter& (Collage) - 07. Lost Language: Selected Poems

Maxine Gadd (Book) - 08. Snow

N.E. Thing Co. Ltd (Photograph) - 09. P + L + P + L = VSI

Iain Baxter& (Print) - 10. North American Time Zone Photo-VSI-Simultaneity, October 19, 1970

N.E. Thing Co. Ltd (Collage)

Project Sites

Discrete project sites documenting the work of specific artists and collectives in detail.

- 01Aboriginal Art in the Sixties

Curated by Marcia Crosby

Research by Roberta Kremer Designed by The Future - 02Al Neil

Curated by Glenn Alteen Designed by Archer Pechawis - 03Expanded Literary Practices

Curated by Charo Neville

and Michael Turner Designed by The Future - 04The Intermedia Catalogue

Created by Michael de Courcy

Research by Sarah Todd Designed by James Szuszkiewicz - 05Transmission Difficulties

Curated by Scott Watson Designed by Dexter Sinister

- 01Aboriginal Art in the Sixties

Essays

Essays and conversation providing a context for exploring the Project Sites and Archives.

- 01Making Indian Art “Modern”

By Marcia Crosby - 02Vancouver Cinema in the Sixties

By Zoë Druick - 03UBC in the Sixties: A Conversation

Edited by Marian Penner Bancroft - 04Siting the Banal: The Expanded Landscapes of the N.E. Thing Co.

By Nancy Shaw - 05Urban Renewal: Ghost Traps, Collage, Condos, and Squats

By Scott Watson

- 01Making Indian Art “Modern”

Video Interviews

Video interviews conducted between December 2008 and May 2009 reflecting on Vancouver’s art scene in the sixties.

- 01Ingrid Baxter with Grant Arnold

- 02Christos Dikeakos with Lorna Brown

- 03Carole Itter with Lorna Brown

- 04Gary Lee-Nova with Scott Watson